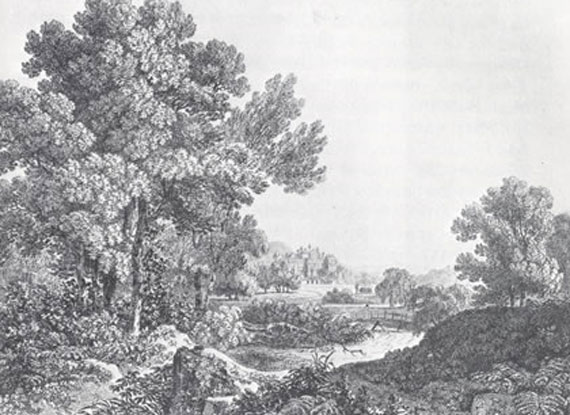

[A Picturesque landscape garden by Thomas Hearne, 1795] Recently reading David Gissen's Subnature, in which a small chapter discusses the social and architectural attributes of weeds, we began to think of what it is to be a weed, which in our own socially defined context, is simply a plant out of place, a human construct, a defect of our perception, and what is its potential function in landscape architecture.

[A Picturesque landscape garden by Thomas Hearne, 1795] Recently reading David Gissen's Subnature, in which a small chapter discusses the social and architectural attributes of weeds, we began to think of what it is to be a weed, which in our own socially defined context, is simply a plant out of place, a human construct, a defect of our perception, and what is its potential function in landscape architecture.

Weeds are often synonymous with "nature." When we see a space left unmanicured and taken over by weeds we refer to it as nature, or wildness taking over. When unintentional seen as a nuisance, but in "nature" a part of the natural system. A nostalgia for wilderness comes easy once it no longer poses a threat. And in the 19th century romanticism of the natural began when the English countryside had been so thoroughly dominated, every acre cleared of trees and bisected by hedgerows, that the idea of a wild landscape acquired a strong appeal, perhaps for the first time in European history.

The weed gives the likes of Emerson, Whitman, Thoreau and generations of American naturalists with a favorite trope—for unfettered wildness, for the beauty of the unimproved landscape, and of course, when in quotes, for the ignorance of those fellow countrymen who fail to perceive nature as acutely and sympathetically as they do.

But are weeds as wild as we think they are? It would seem that the weed, in actuality has evolved in a way in which it benefits the most from the land in which man has already disturbed. In his plowed gardens, in the cracks of sidewalks, in any area intended for a cultivated plant, lies the preferred habitats for weeds.

Frank Lloyd Wright once wrote:

The wielder of the hoe would wonder why weeds couldn't be studied, possibilities found and then possibly cultivated. The "crop" eliminated....Tobacco was a weed once....And tomatoes were once thought by Europeans to be poison....Nearly everything was a weed once upon a time....What vitality these weeds had! Pulsey for instance, Chess (velvet weed), Pigweed....Would the weeds become feeble, if they were cultivated, and "crops" become as vigorous as "weeds" if able to flourish on their own? What of such science and art?

Wright is speaking of this notion of the weed as a human construct, and in fact many of the plants we consider wild weeds today are not actually "wild" but non-native species brought by the first settlers.

Its hard to think of it, but the Indians lived so lightly on the land, that there were few man "improved" areas for weed species to flourish. Many of the weeds we know of today were brought over deliberately: the colonists prized dandelion as a salad green, and used plantain (which is millet) to make bread. The seeds of other weeds, though, came by accident—in forage, in the earth used as shipboard ballast, even in pant cuffs and cracked boot soles.

If you consider the spread of weeds as an artifact of man, then it challenges their presumptuous role as a natural phenomenon, or in urban settings, as reverting back to nature.

What if we were to reverse the roles of certain weeds and plants? Like Wright mentioned, would the plants we so diligently hold dominion over flourish like weeds, and certain weeds act as cultivated plants? What if rather then discerning between weed or plant we designed to allow for a flexible, "natural" takeover of spaces?

[Image by R&Sie(n), Paris, 2008-2009 / I'm Lost In Paris, view of the ferns around the house.]

[Image by R&Sie(n), Paris, 2008-2009 / I'm Lost In Paris, view of the ferns around the house.]

As found in Subnature, and discussed on UrbanTick, the experimental architecture studio R&Sie(n) questions the way nature and molecular nature of cities interact. Stating: "Nature is unpredictable so that it cannot be easily domesticated." But I might add, if nature was to be somehow isolated from man, then its processes in a whole system sense would be rather predictable. Its unpredictability only shown with our intentions of it as a datum.

In the case of the housing project I’m Lost in Paris, the principle is clear: ferns will grow up thanks to the installation of hydroponic system that will feed them. The house will probably disappear and provoke fear to the neighbors.

This house functions as the principle of plants: it is unpredictable, if not to say, self-organizational. It aims at demonstrating that building as well as plants is capable of being changed in response to local or global stresses.

[City on Fire/City in Bloom, by West 8, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 2007]

[City on Fire/City in Bloom, by West 8, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 2007]

In another landscape project, West 8 transforms potted flowers into something containing weedlike images. In a memorial to the bombing of Rotterdam West 8 designed a image of flames out of flowers appearing to consume its surroundings.

In these works, R&Sie(n), and West 8 celebrate the idea of plants as colonizers of space, as unwanted and out of place, in other words, as the "weed," discovering ways to use architecture to bring plants into forms in which they might not belong.