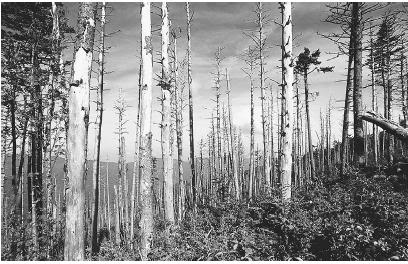

A new post on Yale Environment 360 reports on the large-scale dying off of the world's forests at an extraordinary rate. Much of the death has been attributed by entomologists to the mountain pine beetle, which due to warming winters is enabling their lifecycle to decrease from two to one year, able to produce more larvae in pines of the west. Colder temperatures had once kept the beetle out of higher altitudes, but a slight warming is now bringing devastation to mountaintop forests.

Since 2000, a forest area the size of Washington state has been killed and attributed to insects. But scientists see this as a sympton of an even larger problem of a warming climate. North America has not been the only continent affected, as forests in Australia, Russia, China, and France have been lost to drought, high temperatures, or both. Drought and higher temperatures leave forests ecologies weaker and more susceptable to pests and wildfires.

So the forests across the West are dying, in such large numbers that U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar called it the West’s Hurricane Katrina. In Colorado and southern Wyoming, the U.S. Forest Service has created an emergency management team to cut down dead trees around towns and along roads and power lines. Forest Service campgrounds and trails have been closed because of the hazard from dead trees, and communities surrounded by dead forests have drawn up emergency evacuation plans for residents.

[Dying pine forests, said to be caused by the mountain pine beetle]

[Dying pine forests, said to be caused by the mountain pine beetle]

But what to do? Many of the reasons are still definitively undetermined, and the topic is grossly understudied with large information gaps and uncertainties. The forest deaths are naturally having effects on certain wildlife habits and food sources. But can anykind of human intervention (other then carbon reduction) be done to prevent this widespread forest destruction? As devastating as it may be, perhaps a transition from live to dead forests will manifest into a faster-paced evolution of forest, in which no intervention is necessary. Some species will be lost, while others thrive using the dying material for habitats. Non-native birds will carry non-native seeds more adaptive to the changing climate. New plant material will bring new consumers and predators to these areas.

[Dead trees aren't a total waste, in fact they contribute vital habitats like for these Acorn Woodpeckers]

[Dead trees aren't a total waste, in fact they contribute vital habitats like for these Acorn Woodpeckers]

It’s not surprising that most of us tend to view dead things as undesirable. We impose this cultural bias about dead things to our forests as well. Public land management agencies spend billions annually trying to contain wildfire and insect outbreaks based upon the presumption that these natural processes are destroying the forest by killing trees. Even though there is now some grudging acceptance by land managers that wildfires and insect attacks may be potentially beneficial if they do not kill too many trees, stand-replacement fires, ice storms and large beetle outbreaks are still viewed as unnatural and abnormal—something to suppress, slow and control.

Stated beautifully by Forest Policy Research:

A new perspective is slowly taking root among forest managers, based on growing evidence that forest ecosystems have no waste or harvestable surplus. Rather, it seems that forests reinvest their biological capital back into the ecosystem, and removal of wood—whether dead or alive—can lead to biological impoverishment. Large stand-replacement blazes and major insect outbreaks may be the ecological analogue to the forest ecosystem as the hundred-year flood is to a river.

Such natural events are critical to shaping ecosystem function and processes. Scientists are discovering that dead trees and downed wood play an important role in ecosystems by providing wildlife habitat, cycling nutrients, aiding plant regeneration, decreasing erosion and influencing drainage, soil moisture and carbon storage. “When you start to look at western forests outside of wildernesses and parks, you notice right away that they lack large quantities of downed wood—dead trees,” says Jon Rhodes, an independent consulting hydrologist in Oregon.

Eventually forests, perhaps vastly different in character then their ancestors will form again, a natural part of Earth's longterm cycle of heating and cooling.

I think we're quick to overlook the resiliency of nature, and should take inspiration in it for our own design adaptation. This isn't to say that certain actions should not be taken to subdue man's part in a changing climate, but a design adaptability is necessary nonetheless.

[Related] Natural Pollution